Economic Resilience: Strategic Investments to Reduce Risk

Sasaki

Sasaki

This article originally appeared in the semi-annual journal, RI-Vista: Research for Landscape Architecture. Read the full article here. This is the final article in a four-part series. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3. Pictured above: Flooding in Boston’s Long Wharf. Credit. Download the full issue of Ri-Vista here.

Although the food we eat is likely to cost more due to climate change, the damage caused by higher intensity storms will be the most expensive consequence. By the end of the century, the United Nations predicts that the earth is going to be 4.3 degrees warmer than it is today if we don’t change course. 4.3 degrees of warming translates to about $600 trillion in damage from climate impacts. We must accept that climate-induced catastrophes will be a fixture of our future. That said, the discourse around resilience is primarily an anthropocentric one. While most of the pressing challenges we face in the Anthropocene are ecological, there will also be dramatic impacts on socio-economic inequality. In planning and design, the discourse around resilience embodies a strong anthropocentric element. Most resilience-focused designs preempt plausible future disturbances, especially catastrophic disasters in the most densely populated urban areas. While ecologists view change as a dynamic process, the anthropocentric mindset of resilience-minded design solutions understandably safeguards the present system and maximizes its durability in the face of uncertainties—even though the present system may be flawed.

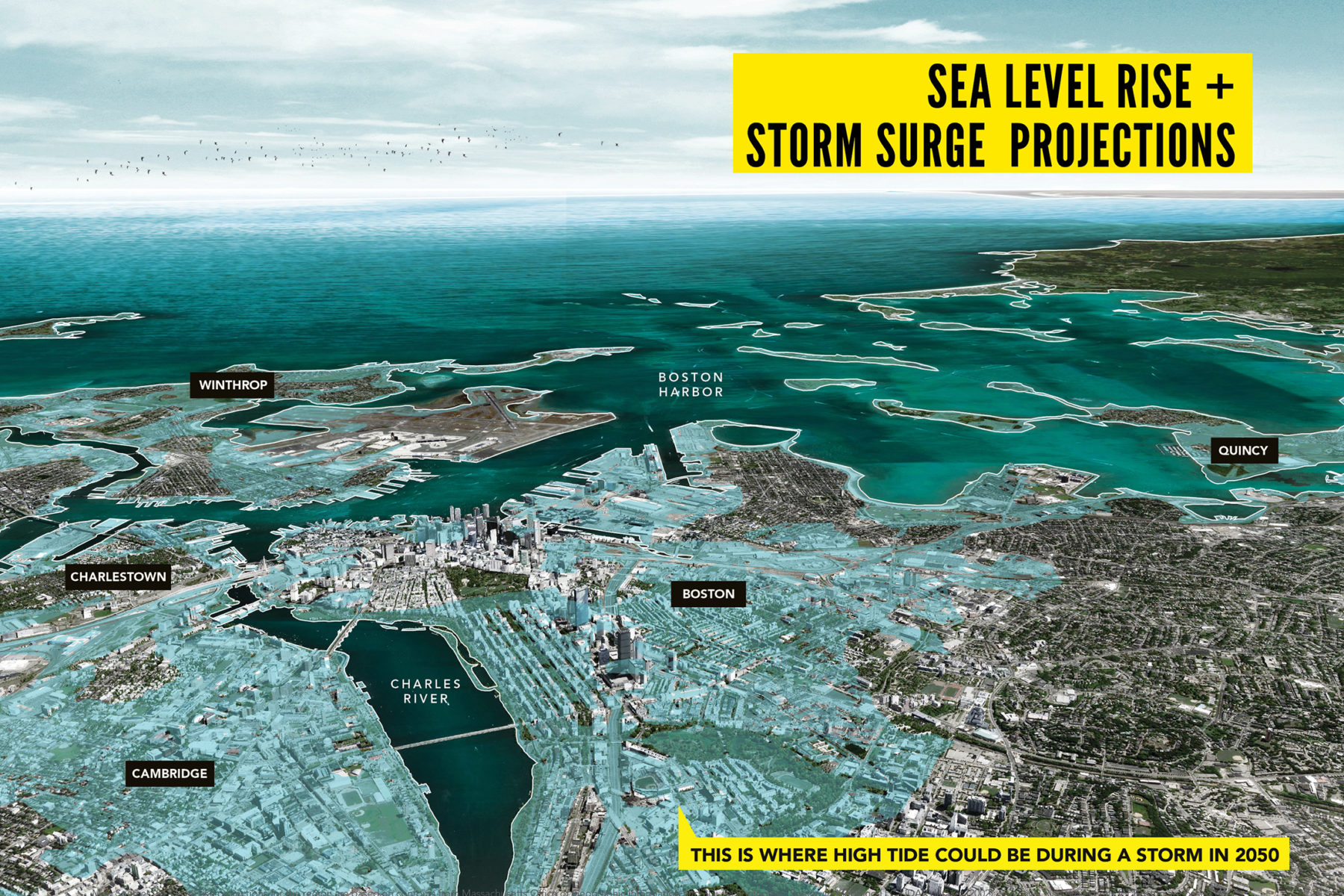

Despite the growing consensus that many coastal areas or floodplains are not suitable for urban settlement and will be increasingly vulnerable and costly amid a rapidly changing climate, it is unrealistic and inhumane to expect cities and settlements to retreat completely. In response to this, we have seen a rise in collective resiliency efforts, such as Rebuild by Design after Superstorm Sandy, Resilient by Design in the San Francisco bay area, and our work mapping sea level rise in Boston.

Cities around the world, including Boston, are beginning to map the impact of sea level rise and other symptoms of climate change as they make long-term planning decisions

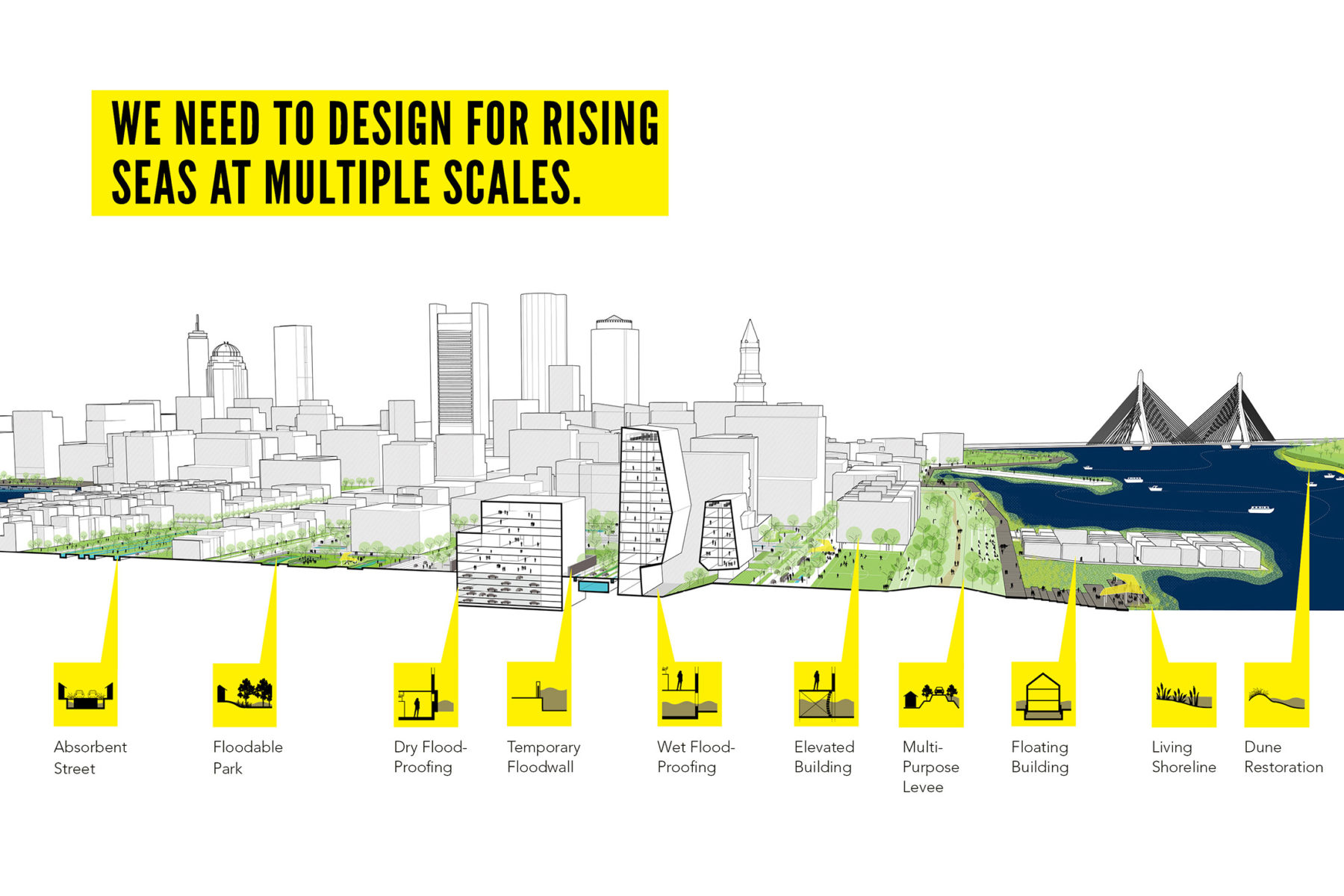

In Boston, sea levels are projected to rise two feet (60 centimeters) by mid-century, and six feet (180 centimeters) by 2100. This new tide line will transform the coastal landscape of the city and increase the probability of a major storm devastating the metropolitan region. Advocating for a long-term resiliency strategy, the design team led the city in preparedness planning at the building, city, and regional scale. Designers also collaborated with experts in engineering, academia, advocacy, and policy making to harness sea level rise expertise and push design thinking further. The study illustrated Boston’s vulnerabilities and demonstrated design strategies to address them, catalyzing a conversation among, city officials, real estate leaders, and academics about a specific call to action: to develop a resiliency plan for the city called Climate Ready Boston, which was unveiled in 2018.

A composition of strategies, rather than any one ‘silver bullet’ solution, must be implemented to mitigate the impacts of climate change

As designers, we need to focus on having a deeper understanding of ecology and embrace our responsibility to promote resilient strategies in order to find a balance between the ecological processes and societal wellbeing. In spite of the world we are leaving to our children and our grandchildren to fix, I am still optimistic. If there ever were a time in history for the design professions to step up, it is now. Everything we do must focus on slowing climate change while contributing to the betterment of society. It is our obligation as designers to provide a meaningful and lasting benefit to the planet, and to humanity.