Grove and Zhang on Design, Ecology, Resiliency, and Research

While ecology and resilience are among the most salient topics in contemporary landscape architecture, their inherent relationship and differences have deep implications on practice

Sasaki

Sasaki

How much right can be done to a wrong? Despite being widely criticized for its environmental impacts, the trend of coastal land reclamation is still prevalent in many regions around the world, especially in developing countries. Some recent reclamation is occurring at such an alarming scale and pace that it is challenging planners and designers with the question: what is the profession’s right reaction to this wrong reality?

The burgeoning consensus of landscape planning and design beyond anthropocentric focus has urged the profession to advocate for environmental well-being more than ever. However design practitioners’ limited involvement of in upstream policy and decision-making imposes sometimes insurmountable constraints on the impacts of our ecocentric efforts. This is particularly prominent when significant missed opportunities are discovered in a project only after the Request for Proposal is issued to the design firm. Land use and the scope are often market-driven and predetermined by various stakeholders prior to our involvement. When a project has a questionable environmental premise, should we participate cautiously and try to make ecological improvements? That is the great dilemma—How much right can be done to a wrong to justify our participation?

Historical precedents are not lacking. For example, one sixth of the entire landmass of the Netherlands consists of reclaimed land – a country where some of the world’s best planning and design has been extensively studied. Or try to imagine Washington DC without its tidal basin or cherry blossoms—the nation’s capital would be missing nearly half of L’Enfant’s iconic plan without reclamation. The land where the Lincoln, Jefferson, and MLK memorials now stand did not exist until 1890. Even here Boston, an influx of immigrants in the 1800s prompted large reclamation projects to create new residential neighborhoods to accommodate the city’s population growth. For fifty years, day and night, trains brought in about 3,500 railroad cars of gravel each day to fill the Back Bay. What if Frederick Law Olmsted never had Commonwealth Avenue to complete the Emerald Necklace? Today one sixth of Boston is built on reclaimed land. While we applaud Olmsted’s great vision, we know that these culturally significant landscapes were designed and built on ecologically unsound principles. But where should we draw the line? Should we do nothing, resentfully, or do something that might have lasting positive impact? It might be easier to walk away with our heads buried in the sand. But if that were the case, would Boston’s Back Bay have been different today? And would the Fens have been covered with development decades ago without Olmsted’s intervention?

Forest City’s edge conditions strive to restore mangrove habitats and improve regional water quality

There are, of course, some encouraging cases where designers have successfully addressed development decisions that could have had even more severe ecological impacts. Check out Forest City in Malaysia and the Xincunsha New Community in China for some of Sasaki’s solutions and responses to these challenging contexts. Both projects share some similarities with the Back Bay, where a booming economy and rapidly expanding middle class are demanding new places to live, work, and play. When an emotional argument about environmental ethos is not likely to win over economic forces, should we just walk away, or should we participate in an attempt to make incremental ecological improvements? In our work, we often find ourselves celebrating the old Chinese proverb, “the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, and the second best time is NOW.” At Forest City Malaysia, even within the constraints of an intensive land use and development program, our masterplan strives to preserve 250 hectares of critically endangered habitat and maximizes ecological functions along the coastal edge of the reclaimed islands. At Xincunsha, we successfully convinced the developer and the local government to forgo a plan for two privatized golf courses in favor of a public park and a wetland education park that will benefit the larger community. In the end, the economic study and the undeniable facts on the parks’ ecological benefits made it a win-win outcome for both the developer and the environment. The design intervention also took sea level rise into consideration to better prepare the development for the major challenges in the future due to climate change.

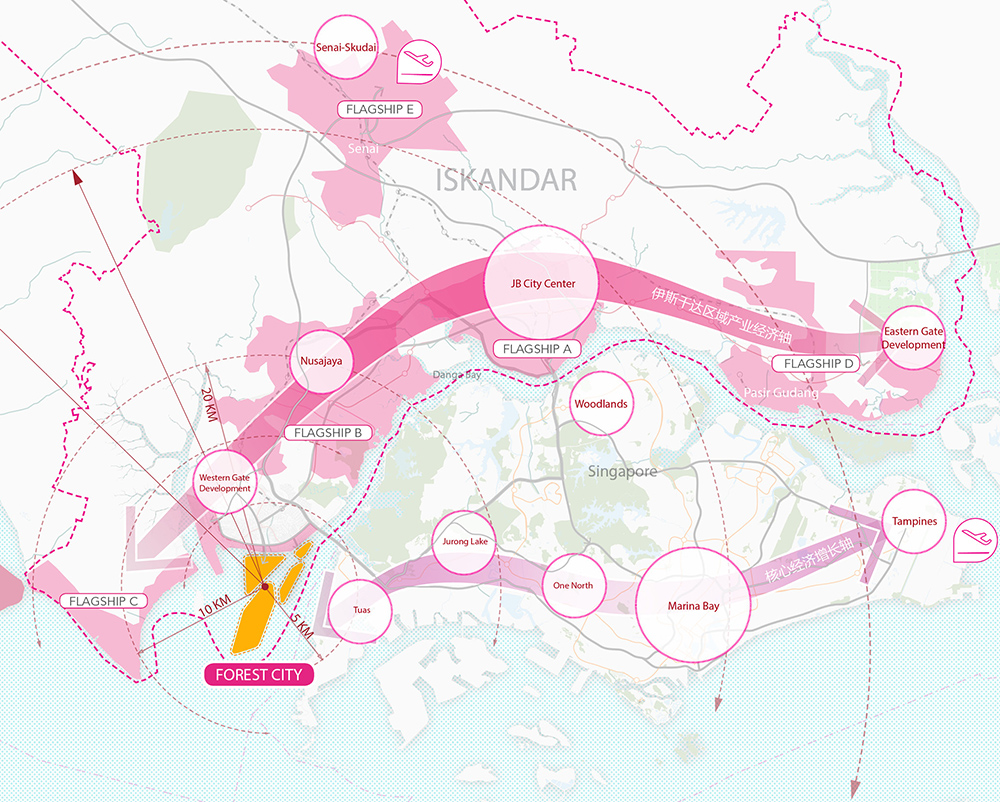

Regional context of the Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore with strong connection through the causeways

These large scale challenges and opportunities are not only occurring in developing countries. Due to climate change, it is critical to reexamine coastal cities at a much broader scale, including the aforementioned culturally significant landscapes in Washington DC and Boston. For instance, some of world’s best design professionals participated in the Rebuild by Design competition initiated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, with the goal of envisioning the best solutions to increase resilience across these vulnerable areas. Referencing the history no longer suffices the future needs. To ecologically adapt these well-established cities in the global north will inevitably incur major costs. How to finance these adaptations will be equally challenging and require innovative solutions.

Forest City’s economic positioning

Thinking idealistically, we wish that economic drivers would not be an overpowering force for land reclamation, marginalizing the consideration of environmental degradation. We wish that the world had not lost over a third of its wetlands in the last 200 years. We wish part of Manhattan could be restored to its native salt marsh habitat. These examples may remain a conundrum for the profession until we build a stronger voice, along with the allied professions, during the highly politicized land development decision making process. If the reality of ongoing coastal land reclamation prevents us from planting a tree twenty years ago, at least let’s plant one today by scrutinizing possible opportunities to intervene. We believe that incremental ecological improvements can make cumulative positive impact on the environment, or even offer an opportunity to address the future challenges due to sea level rise. Sometimes we never know the opportunities that are unleashed unless we have tried or fought to make a difference, but how to pick the right fight is an art onto itself. We pose this question to our peers, and welcome more innovative solutions to the not-so-ideal reality of the present. The answer lies in our profession’s collective action.

This post is based on a presentation delivered by Michael Grove and Tao Zhang at the ASLA annual conference in 2015. Special thanks go to Sasaki Principal Jason Hellendrung for the valuable feedback on sea level rise and Rebuild by Design.

While ecology and resilience are among the most salient topics in contemporary landscape architecture, their inherent relationship and differences have deep implications on practice

Economic resilience and ecological restoration fell hand-in-hand—the success of one goal relied on the success of the other at Gulf State Park