Getting Real About Virtual Reality

Using technology to help clients understand the intricacies and features of a design

Sasaki

Sasaki

As virtual reality (VR) technology becomes more prevalent in the design process, we are beginning to tackle the challenge of optimizing its efficacy. Being able to immediately place ourselves into a conceptual universe is a fascinating experience, but special consideration should be taken when implementing VR practices.

Whether as a tool for public engagement, client involvement, or internal review, technology must be the foundation that design stands on. If the flashy attraction of VR supersedes the accurate communication of the concept, or leads to a dead-end “what’s next” moment, it has not done its job. At Sasaki, our Data & Design Tools team designs context-driven, nuanced VR tools and experiences to address specific scenarios—a few select case studies showcase ways that these unique engagements have helped us explore, fine-tune, and communicate our work.

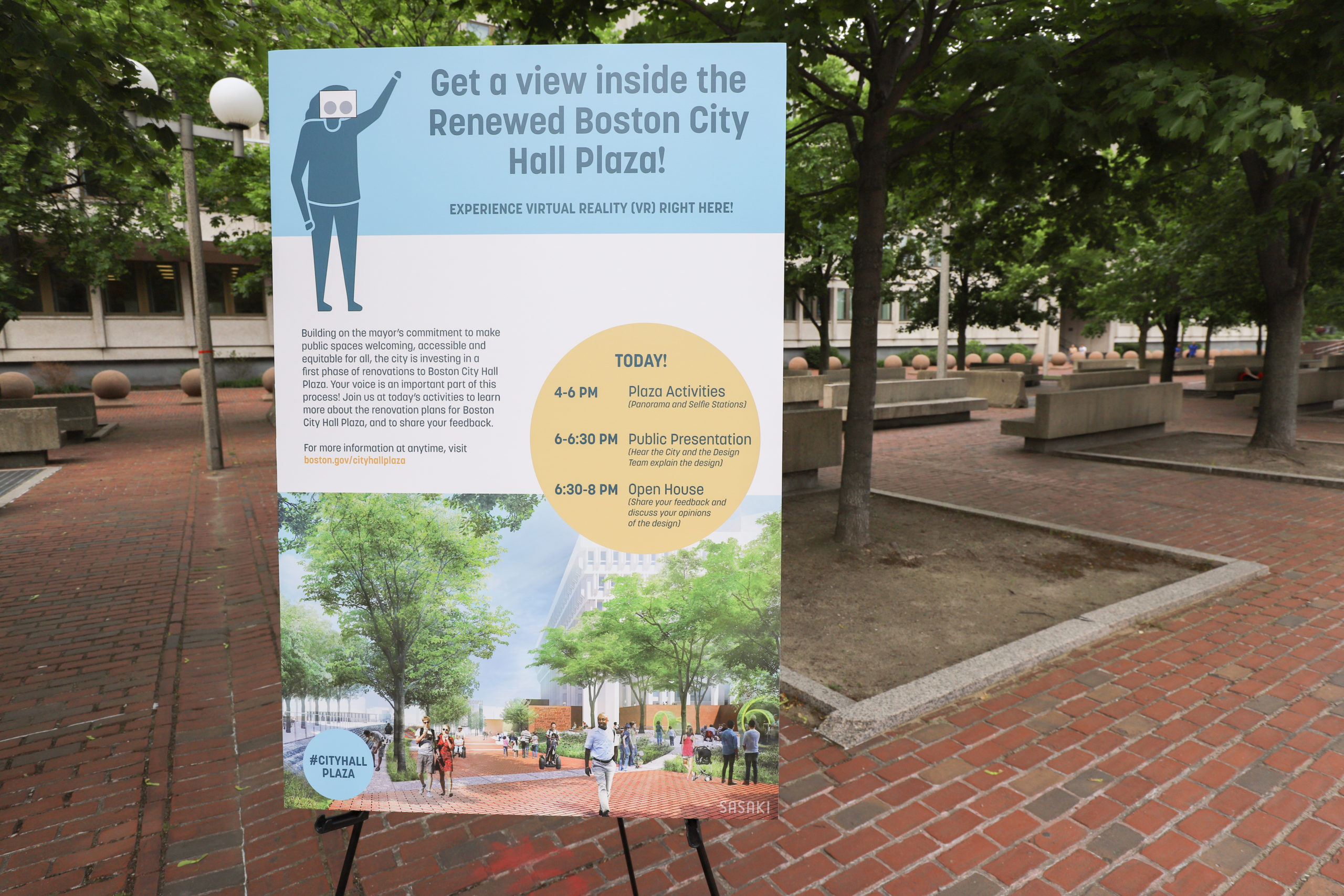

Providing VR technology at public engagement events encourages people of various ages, language backgrounds, and education levels to interact with designers’ visions for civic and cultural spaces. As part of the public engagement phase at Boston City Hall Plaza, virtual experiences of the new plaza design—right on the plaza—helped our team start conversations with passersby, giving the public a better platform to interact with the spatial designs we’re bringing to this civic space.

While traditional forms of public engagement like surveys are great tools for collecting data at the beginning of a process, they can sometimes discourage open-ended onsite dialogue with designers. Similarly, standard 2D renderings of design options can sometimes be difficult for viewers to interpret and give feedback on because they can’t immediately place the rendering in space or understand what has been changed.

To find new ways to bring the design to life during the public engagement process, Sasaki equipped two VR stations at the plaza with mobile, lightweight Oculus Go headsets.

These easy-to-use headsets enable users to quickly experience a “before-and-after” moment by comparing the existing view of the Plaza to the one they find in their VR headsets. The design team chose two locations within the plaza to engage passersby with VR, and staffed them with multiple design team members. Visitors who didn’t want to put the headset to their eyes could view the same 3D rendering via iPad or on their phones, making the interaction accessible to all.

The first VR station highlighted the difference between the existing plaza’s inaccessible brick terraces and vast open space. It also highlighted the new design’s universally accessible sloped walkway, which is lined with trees, plantings, and an interactive water wall. As visitors held the Oculus up to their eyes, removed it, and held it up again to spin around in the new space, they asked questions and shared insights with the design team. One young viewer mentioned how the new space felt “cozier,” and several remarked on how the clear pathway made sense of a currently confusing space.

The second VR station captured the existing closed north entry, adjacent to an existing bank of granite steps.

Here, visitors shared exclamations of “wow!” as they experienced the space transformed into a welcoming new entry and courtyard, and then turned to see how a destination playscape enhanced the slope at the granite steps.

Visitors took in the details, asked questions of the design team, and pulled the headsets up and down to compare the views. The most common question was, how soon could the city expect to see the new plaza open?

To supplement the VR stations, the engagement also included “selfie stations” in the plaza. These banners provided visitors with large format renderings and descriptions of the new plaza experience and the ability to capture an image of themselves in the renovated space. Design team members staffed these stations, answered questions, prompted visitors to experience the VR, and invited them to join in the formal public meeting that evening. Bringing all of these digital and analog components together helped users understand aspects of the design that might have been misunderstood by just interpreting a typical plan or section.

In client meetings, designers may be tempted to lean on VR to present a completed, polished representation of a built space to dazzle the client. Sasaki views VR as an opportunity to push design thinking to be more collaborative and inclusive, using virtual reality as a modeling opportunity to dig deeper into the design process alongside the client.

However, it can be challenging to naturally integrate VR into a client meeting. Sometimes the technology becomes distracting, which breaks down the relationship between the viewer and the presenter. In order to have a seamless presentation experience during a review session with the Lawrenceville School client team, Sasaki developed multi-user content that naturally encourages communication between team members.

In preparation for a review session, Sasaki’s in-house developer team used VR to envision the Gruss Center For Art and Design as well as the new Tsai Dining and Athletic Complex, two projects that Sasaki is implementing as part of our larger master plan for the school. It was challenging for the team to represent the myriad of ways people can interact with these new campus amenities via 2D modeling, but bringing VR to the client gave them a new window into each building’s complexity.

By enabling a multi-user feature, Sasaki team members guided the clients through a tour of the rendering’s key components. Because the Sasaki team and the client team both had the ability to view the design and use a clicker to point to specific features, the discussion flowed naturally while the experience remained immersive.

The virtual tour of the space gave the client a more nuanced perspective on the design: team members were surprised by how big the space felt, and glad to see the logic of the design layout from an immersive point of view. After the review session, the client was interested in acquiring VR headsets of their own in order to continue interacting with the content we created.

Explore the maker spaces within the Gruss Center for Art and Design here, and check out the sports and dining facilities for the Tsai Dining and Athletic Complex here.

With technology developing faster every day, Sasaki plans to leverage VR as a design thinking tool that naturally extends the design process and helps design teams address spaces’ complex functions for their communities. Public places like Boston City Hall Plaza host a range of events, from daily playtime activities for local families, to citywide protests, to picnics for City Hall employees. The Lawrenceville School must cater to the dynamic needs of students and faculty who work in these living-learning communities. As designers finding new ways to enrich engagement with clients and communities, VR technology acts as a window into the design process that helps teams build a more collaborative vision of these spaces.