Rutgers University, University-Wide Physical Master Plan

Multiple Campuses, NJ

Sasaki

Sasaki

Cause and effect, while intertwined, rarely present themselves in obvious ways. When we began work on the master plan for the main campus of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ, we soon learned that a key driver in determining planning solutions for the campus would involve resolving issues associated with the overtaxed bus system. This early realization led us on an analytical journey that would uncover the underlying causes of the symptomatic bus problem.

After a year-long planning exercise, we arrived at an integrated system of solutions for the master plan, which we finalized in 2015. Now, a few years later, the recommendations developed in conjunction with the University have started to bring about positive change for the campus community—in particular, its students.

This article will detail the story of our discovery process and how we arrived at the recommendations for Rutgers 2030, the master plan we created for Rutgers. First, though, a brief detour through the history of Rutgers will help set the contextual stage.

Founded in 1766—a decade before the signing of the Declaration of Independence—Rutgers University is the 8th oldest institution of higher education in the country. Over the years, it has taken many shapes, evolving from a small ecclesiastical school to a land-grant college in the 1860s to the designated state university of New Jersey in 1945. Under the state university system, New Brunswick remains the main campus; there are two additional campuses in Newark and Camden, and, with the integration of the former University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Rutgers created Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences (RBHS), with locations in New Brunswick and Newark and throughout the State.

Like many large state universities, the New Brunswick campus is programmatically and geographically diverse. Unlike many large state universities, however, the New Brunswick campus is composed of five distinct and distributed academic districts, a formation that developed organically throughout the University’s long and storied history. Previously, each of these districts operated as individual residential colleges, offering then-students a compact educational experience around the core of that specific campus. While this system was spatially convenient for students, it did not fully leverage all of the University’s growing offerings. In response, a campus-wide liberal arts college was created in 2006 to better serve students across all districts.

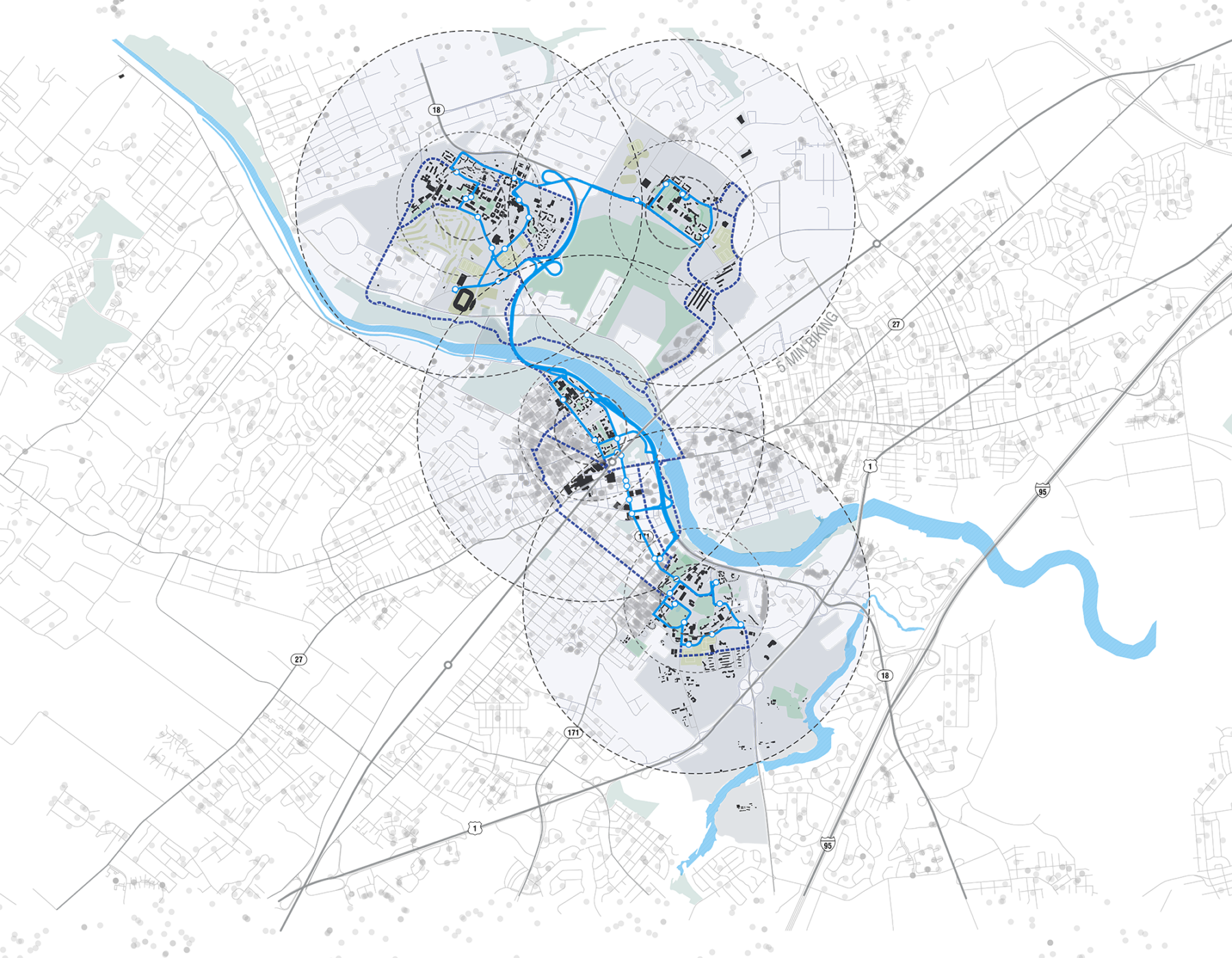

Rutgers’ academic districts—previously individual colleges—are spread across five square miles, representing significant transit challenges

This consolidation realized educational efficiencies, lending a stronger sense of cohesion and interconnectedness among the districts. It also presented operational efficiencies—such as standardized admissions and graduation requirements. Yet, these efficiencies came at the cost of unintended consequences. The districts, which are physically separated by a highway and the Raritan River, cover five square miles and require a major transit system. Today, the student experience is in part defined by daily student travel, as many students must trek between the separate districts to attend classes.

It follows that the most telling symptom of these challenges is the University’s extensive bus system. In response to the students’ growing transportation needs, the University was treating the symptoms—not all of the causes—by adding more and more buses. The increase in vehicles added to the already congested traffic, which paradoxically reduced the effectiveness of the added buses. It was this Catch-22 that Rutgers presented to us, which, in turn, prompted our deep dive analysis.

There is an old design and problem-solving method, credited to the founder of Toyota, Sakichi Toyoda, known as the “Five Whys.” Straightforward in its approach, this technique uncovers the underlying causes of a perceived problem by asking “why?” a given issue exists, and continuing to ask “why?” to the subsequent answers. Tempered with guiding hypotheses and professional experience, this method can often yield valuable insights.

Applied to Rutgers, asking “why” helped the team cut to the heart of the transportation problem. Why was the current system not working? Because students’ complex travel needs weren’t being adequately served. Why did students have such complex travel needs? Because they might have classes on five separate campuses, with little logic tied to their housing and scheduling choices. Through a series of questions, we discovered the broader issues contributing to the perceived issues of busing. Using our MyCampus tool—a qualitative survey distributed to students and faculty to gauge their interaction with the spatial and programmatic areas of the campus—the answers to our “whys” were backed by first-hand experiences.

Equipped with the data from the MyCampus survey, we wanted to test our hypothesis that students lack the necessary information to make informed scheduling choices. Namely, we wanted to get a better sense of whether students have an accurate idea of how long it would take to travel from classroom A to classroom B. We had never utilized our data analysis to tackle this sort of problem before, so we set about devising our own approach. Tapping into a previously latent set of data, we pulled the complete scheduling data for every student enrolled in a given semester. We scrubbed the data to ensure anonymity and created a trace that amassed each student on a campus map, traversing space in accordance with their schedules. Nicknamed “The Swarm,” this analysis shows us a very clear pattern: students were moving between the districts far too many times, and often in unrealistically short intervals. Rutgers did have a busing problem. But our analysis demonstrated that, because of poor coordination between the systems responsible for scheduling, registration, housing, and parking, what Rutgers really had was a logistics problem.

The implications of this circulation issue were staggering. We observed certain students, represented as single dots in the tool, ping-ponging between the districts four or five times a day. What impact does such a hectic travel schedule mean for a students’ ability to concentrate in class, not to mention their overall attendance?

Having discovered the array of issues that were impacting the student experience, our team began to develop a series of solutions. The resulting master plan recommended a layered approach to mitigating these issues, including:

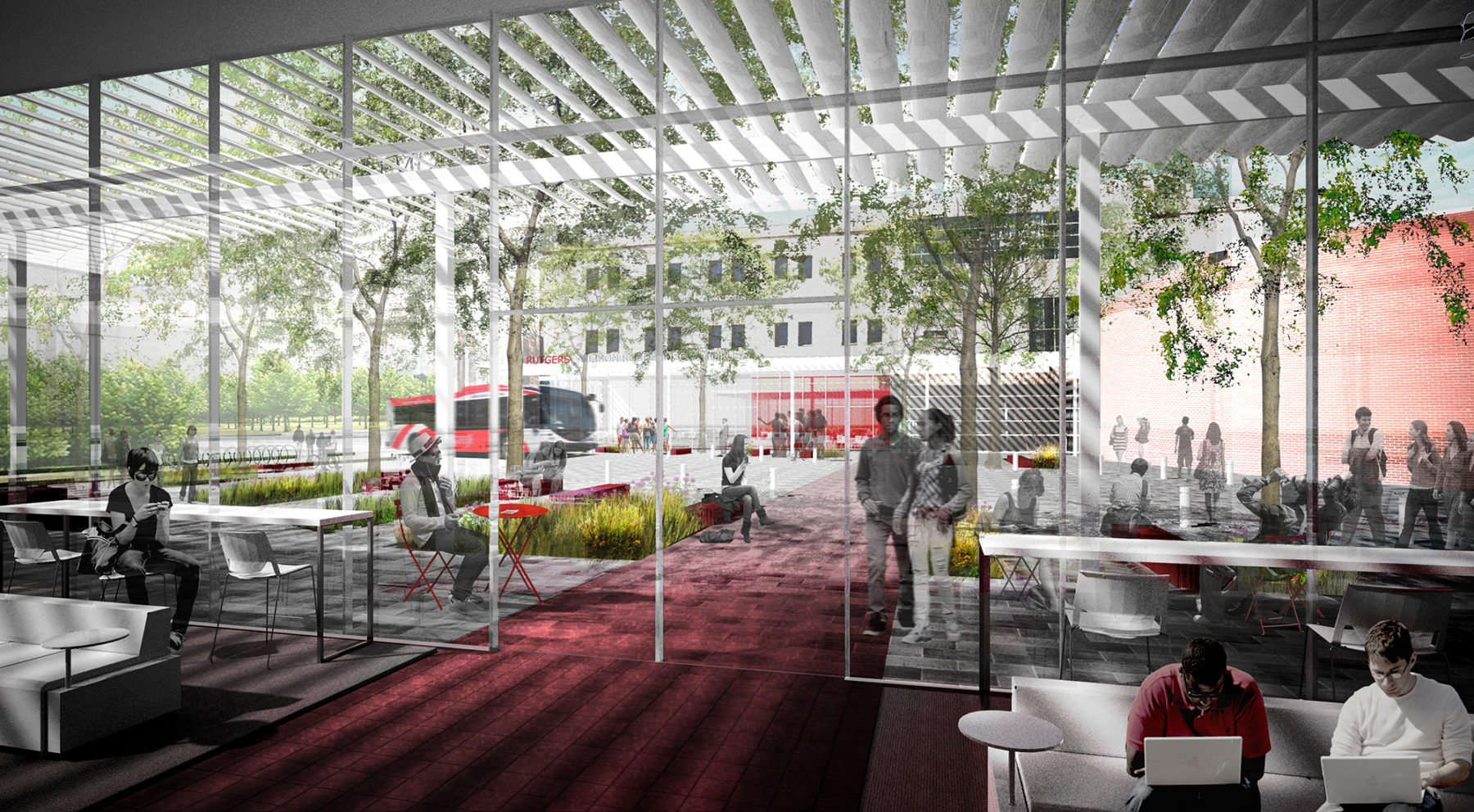

A view from inside one of the proposed transit hubs, showing space to study, socialize, and wait safely for the bus

Planning projects are strange creatures. Quite different from the usually linear design and construction of an architecture project, master plans can often take five, ten, even twenty years to be fully realized. Since we had wrapped up the plan for Rutgers a few years back, we recently sat down with Paul Hammond, Rutgers’ Associate Vice Chancellor for Technology and Instruction, to get an update on how things are beginning to take shape. Of the three major recommendations listed above, Hammond updated us on major strides forward with two of them.

Sasaki’s initial recommendation for a scheduling program that optimizes by location has been confirmed by a specially-appointed President’s Taskforce. The University is currently working with outside vendors to develop the program. The goal is to schedule course locations based on an analysis-based “best guess” of which housing area or other location that the majority of students for any given class will come from. This approach will be supplemented by block scheduling classes that students often take in the same semester. Most first year biology students, for example, take General Biology, General Chemistry, and Calculus 135. With this in mind, it makes good sense to schedule these back-to-back in the same, or at least nearby, classrooms—rather than, as can be the case, at the same time on separate campuses.

While they expect to begin using this advanced classroom assignment software in 2018, Rutgers has already rolled out one major initiative to curb students’ intra-campus travel. As of the fall of 2017, when students schedule their classes, they are able to view their “optimal schedule” based on location and necessary travel time. Already, within just two semesters, the campus bus system has seen an 8% reduction of course-related travel due to this change.

The master plan recommends siting transit hubs to enable students to walk to most academically critical facilities within five minutes

The other major innovation is technology-enabled synchronous instruction. Following our general recommendation, the University put together a team of experts to explore how this mode of instruction might work and to create design standards. The idea is for students to have the ability to interact with their instructor in a distance-learning setting. Since the goal was to reduce student travel time, one of the major challenges was devising a system that could work for large classes. Video conferencing for small groups is pretty well ironed-out, but seamlessly splitting a 275-student lecture class into two classrooms on separate campuses had never been done before.

After much planning, Rutgers tested this new mode of instruction with ten courses in the spring semester of 2017. You can read more details on these classrooms configurations on Rutgers’ website. The pilot courses for this first semester were chosen both by geography—classes that traditionally require students to travel to separate campuses—as well as a diversity of subject: courses included Introduction to Kinesiology, an intro business class, and Theater Appreciation.

After just one semester, the project has been a hit with students and instructors alike. The solution is simple yet effective, with a big boost from the latest distance learning technology: two classrooms are outfitted with identical state-of-the-art audio/video equipment. Students attend whichever classroom is more geographically convenient for them, while the instructor alternates between the two classrooms. A life-size video stream of the instructor is broadcast to the other classroom, and a view of the students is broadcast to the instructor’s classroom. And the students in each location are able to see and talk to their classmates in the other location. The result is a successful virtual environment where everyone sees everyone, with the instructor having the ability to call on students in the other location when they raise their hands.

As futuristic as this may sound, it has been a seamless roll-out so far. “I like that [the instructor] is able to see both classrooms and you can ask questions and the instructor can hear you,” said a student in a recent article on the classrooms. “And I spend less time traveling to get here.” One striking result from a survey at semester’s end suggested that 50% of students who responded would not have taken the class if they had had to travel to the other campus.

Likewise, a kinesiology professor who was a pilot instructor for the classrooms this past semester, said “I can still write on the board, I can still show animations of muscle contractions and pull up an image of an obese mouse and show what leptin deficiency looks like. I still feel like I have the full range of motion with the things I can do in class.” And anecdotally, several instructors reported that students in the remote classroom were paradoxically more likely to ask questions, implying that the digital “distance” might actually reduce classroom anxiety for students.

Though Rutgers has only been fleshing out this master plan for a few years, it’s very exciting for us to see the major wins they’ve already achieved. This planning project is indicative of the value of a great relationship between client and consultant, and the importance of an objective lens in determining the underlying causes behind perceived issues. We’re honored to have taken the journey of discovery with Rutgers University.

Sasaki developed Rutgers 2030 in association with RAMSA. Sasaki’s efforts focused on data analysis and the development of the software, synchronous instruction and transit concepts described in this article. You can read more about the plan here, and feel free to contact Greg Havens or Ken Goulding to learn more about Sasaki’s planning practice.