Cool Spot Pop-ups Offer Bostonians a Respite from Heat

Part of the City of Boston Heat Resilience Study, these pop-ups will hold community events throughout the summer

Sasaki

Sasaki

To preserve the vitality of the public realm and protect the wellbeing of their residents, cities with warm summers or year-round climates need to plan for extreme heat, just as those on oceans must plan for rising sea levels. Fortunately, urban planners, architects, and landscape architects are developing models and tools to fortify the public realm for extreme temperatures.

It’s hot. 2023 was by far the warmest recorded year on the planet, and 2024 is on pace to beat it. For half a century, humanity has known that climate change would be the inevitable consequence of burning fossil fuels, but in the past decade, its reality has sunk in. Climate change is here, and if you go outside, you’ll probably feel it.

If you go outside in the city, you’ll probably feel it even more. That’s because of the urban heat island effect—cities running hotter than surrounding areas by up to 7°F due to the clustering of buildings and pavements that absorb and radiate heat. With the onset of more severe climate change, urban heat is pushing temperatures in certain parts of cities into dangerous and even deadly ranges.

Cities are vital places in the modern world because disparate currents converge there. In healthy cities, people of all backgrounds regularly cross paths, interact, and influence one another in the shared spaces between buildings, also called the “public realm”—everything from parks, to plazas, to sidewalks, to the buses and trains of transit systems. The churn of this melting pot is what generates new ideas, enterprise, culture, and social movements. But if that melting pot is, well, melting, people either stay indoors or else must risk their health and lives outdoors, and the vital exchange of the city starts to melt away too.

“The outdoor experience of heat is not just about nice places for people to gather for a picnic or a concert,” says Sasaki Director of Sustainability Tamar Warburg. “It’s about work. A lot of people work outside—gardeners, roofers, construction workers and delivery workers—and those people are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat. It’s about recreation. People run outside, they play outside, they exercise outside. It’s about commuting. If you’re waiting at the bus stop, do you have shade?”

To preserve the vitality of the public realm and protect the wellbeing of their residents, cities with warm summers or year-round climates need to plan for extreme heat, just as those on oceans must plan for rising sea levels. Fortunately, urban planners, architects, and landscape architects have begun to undertake this immense task, and each day are developing models and tools to fortify the public realm for extreme temperatures, creating a new guidebook for summer urbanism.

The outdoor experience of heat is not just about nice places for people to gather for a picnic or a concert. It’s about work...It's about recreation...It's about commuting.

Tamar Warburg

Climate change is a global phenomenon. Regardless of where we live on the planet, we have all experienced it. Heat, however, is not felt evenly—not only across latitudes, but within cities themselves.

“Your heat experience is determined not just by weather, but by the built environment around you,” explains Warburg. “Are buildings radiating heat or protecting you? Are you near cooling features like parks and trees? Do you have the financial ability to install air conditioning? That physical environment is very much a result of neighborhood history and systemic racism over time.”

As Warburg points out, neighborhoods that have been historically discriminated against and disinvested in—those without cooling features like green space and air conditioning—are in much greater danger of overheating, and therefore in greater need of investment in cooling strategies now. It is imperative for cities to prioritize these neighborhoods when they address the crisis of urban heat.

One city that has recognized that imperative is Boston, which commissioned Sasaki to draft an official heat plan, completed in 2022. In analyzing the city’s geographic and social context, Warburg and other Sasaki researchers discovered that neighborhoods that were historically redlined—that is, denied access to mortgages and loans because racist government and bank lending practices deemed them too poor or too Black for investment—are 7.5°F hotter during the day and remain hotter at night than wealthier and whiter parts of the city. They also had 74 percent less park area and 30 percent less tree canopy, physical embodiments of generations of institutional discrimination and disinvestment.

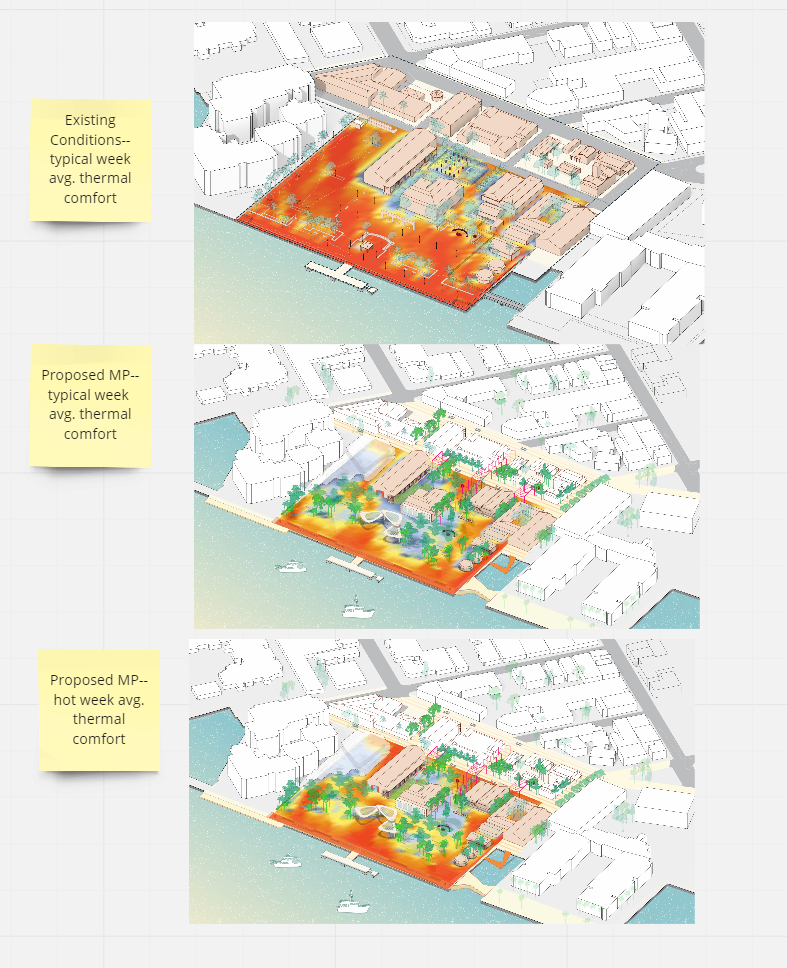

In addition to ten-thousand-foot historical analysis, Sasaki’s Boston heat plan studied the effects of heat at a granular, street-by-street level in the present day. Designers walked the block with local residents in five of the most heat-vulnerable neighborhoods in Boston and sketched out rough diagrams of places to add shade, take advantage of existing breezeways, and insert seating according to their guides. They then turned these sketches into models and analyzed their impact on thermal comfort—the way the human body experiences heat—and to demonstrate that the interventions requested by residents would in fact lead to cooler streets.

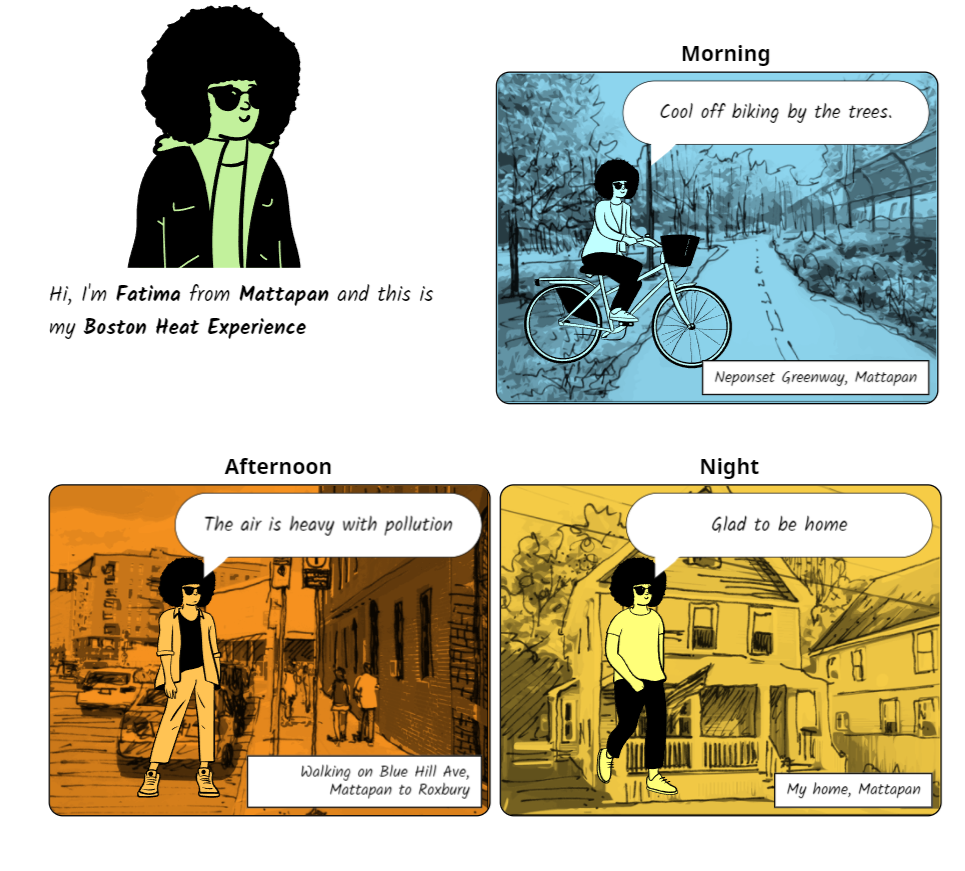

For Boston’s Heat Plan, Sasaki encouraged residents to narrate their experiences of heat in the city using comics

In addressing urban heat, it’s important to start with and center people in the planning process to ensure that citizens’ needs and behaviors are thoroughly understood. The success of an intervention should be measured by its ultimate impact on people and their quality of life. Planners undertaking the urban heat problem should appreciate the utility and limitations of common heat metrics and make sure their decisions are informed by the best available data.

Once planners understand the social context of a city’s heat experience and figure out where to prioritize cooling strategies, the next question is how to implement those interventions. The main objective here is usually relatively simple: shade.

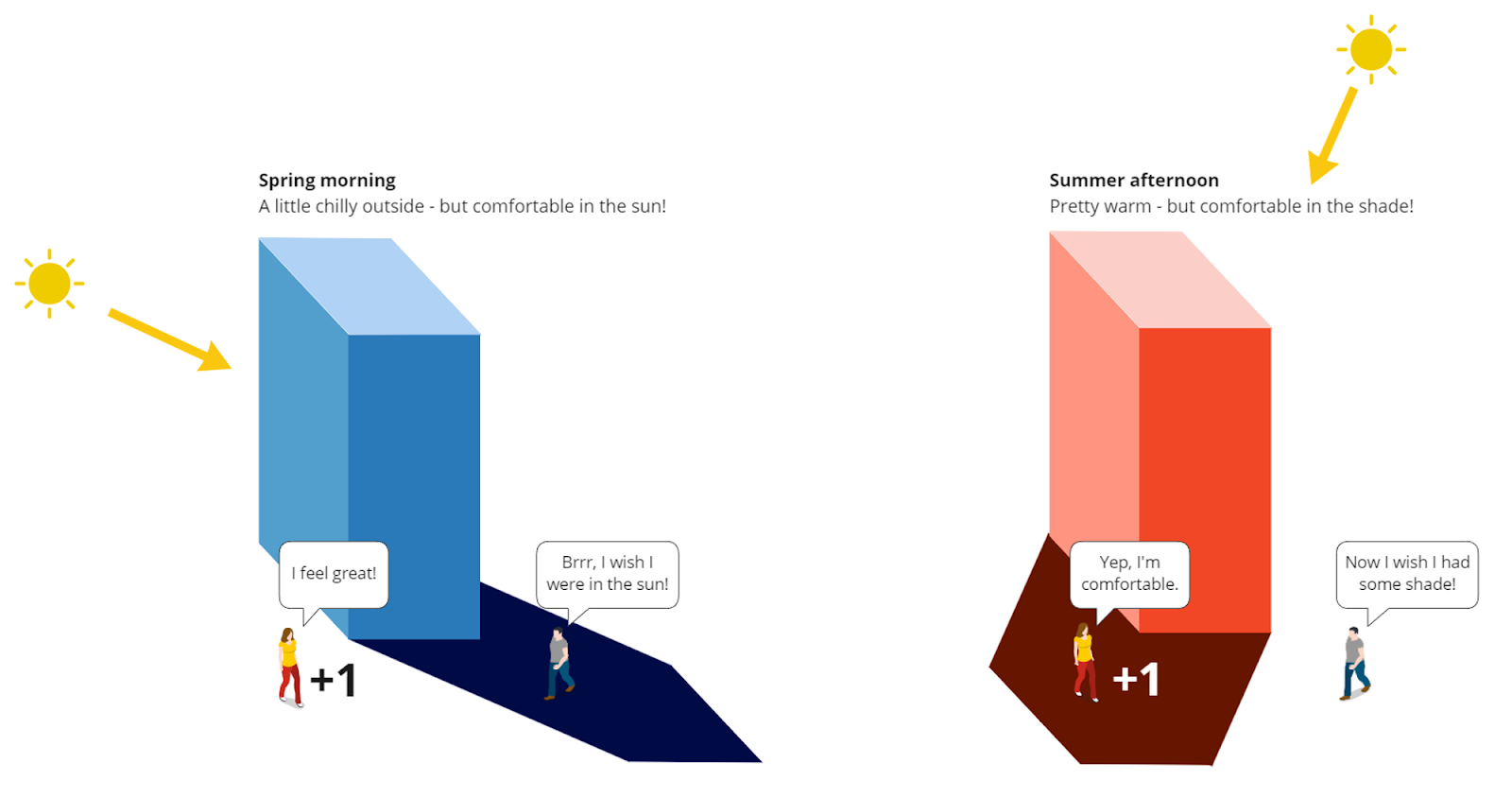

But when designing for regions that experience wide climatic swings from summer to winter, the placement of shade can get more complicated. Sasaki senior design technologist Scott Penman explains: “I can tell you if a point’s going to be in shadow, but without some understanding of the region’s climate, then I don’t know if that’s a good shadow, bad shadow, or inconsequential shadow.”

The thermal comfort of shade is contextual

A good shadow is one that will cool you down when it’s hot. A bad shadow is one that chills you when it’s cold. When it gets too hot or too cold for a shadow to make a difference, shade is inconsequential. Modeling all of these conditions to ensure the most comfortable public realm through the year is where hard data comes in.

Designers use aggregated climate data to calculate a measure of thermal comfort called the universal thermal climate index, or UTCI—a measure of how weather “feels” that incorporates temperature, humidity, and wind speed. Sasaki then uses UTCI to map thermal comfort across its designs with NeedleMovers, a software tool developed in-house by Strategies, our technology R&D team. NeedleMovers can be used before, during, or after the design process to model thermal comfort, but according to Penman, the earlier, the better.

“NeedleMovers creates compelling storytelling to advocate for basic cooling elements,” he says. “We could ask our clients to include an awning or a roof structure or a tree all day long, but if we can create a graphic to show them how those features make a place more comfortable, it becomes a no-brainer.”

Sasaki designers employed NeedleMovers to lay out tree and shade structure placement in Mallory Square, a public plaza at the sunny tip of Key West, Florida

As our planet gets hotter, however, the aggregate climate data designers use is becoming increasingly outdated. To account for this and plan for a warmer future, designers use climate prediction models to “shift” their weather data. But in the meantime, they’ve also become more adept at deploying sensors on-site to verify the weather models they currently have.

One place that’s happening is on the Sasaki headquarters roof in Boston, where staff have installed a weather station that measures temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, wind speed, rainfall, and particulate matter, among other indicators. Collecting this hyper-local data is an experiment in verifying climate modeling predictions. As Penman puts it, “We’re using this building to make sense of this data. We inhabit it, so we can correlate combinations of weather data with our own experience. I know what 80 degrees feels like on the street—does it feel the same if I’m on the roof in certain wind conditions? The sensor helps us quantify that.”

Sasaki’s SenseCAP ten-in-one rooftop weather station

Armed with ground-level planning context and UTCI modeling, designers can draw from a toolbox of summer urbanist tactics to create a cooler public realm. The best strategy is not to climate-control the entire city, but to create pockets of cooler microclimates connected by a web of cooler paths.

“Thermal comfort isn’t rocket science,” says Sasaki landscape architect and principal Michael Grove. “It’s really about shade, and ideally shade through trees, because evapotranspiration helps to cool the environment as well.”

At the site level, planting deciduous trees is the most versatile way to cool down a street or plaza, as they provide shade in the summer while admitting sunlight in the winter. In public spaces, landscape architects try to use species with bigger leaves to provide more coverage. And as Grove says, trees’ evapotranspiration—a cooling process of water evaporating from leaves, much like sweat evaporates off our skin—also brings temperatures down.

If planted strategically, trees can also be used to guide upper-level winds down to the ground and create comfortable breezes. Grove’s design team used this tactic in their plan for the Saigon Riverfront in Ho Chi Minh City with a tiered series of trees arranged tall-to-short to funnel air flow down to the street level.

Trees serve several cooling purposes in the plan for Saigon Riverfront

At the city level, networks of tree-filled parks connected by tree-lined streets can scale up the cooling effect of a single tree for an entire neighborhood, significantly reducing the urban heat island effect with park cooling effects. A dense canopy on a city street can bring temperatures down by more than 5°F. That’s why some cities, including Boston, are creating urban forest plans, and passing legislation to curtail the loss of existing tree canopy, especially in formerly redlined areas.

Cities should also prioritize shade at bus stops and outdoor train stations—essentially, anywhere where people might be waiting or gathering for extended periods of time. If trees aren’t practical, an awning or purpose-built shade structure can do the trick. For the Boston Heat Resilience Plan, the City coordinated with the local transit agency to develop a toolkit that recommends certain shade structure placements based on the sun’s orientation to bus stops.

From the Bellagio to a mini-golf course, everyone loves a fountain. But fountains aren’t just soothing to watch and listen to—their mist also cools down their surroundings.

In Sasaki’s highly-anticipated Ellinikon Park—a 600 acre urban park under construction on the site of a former airport in Athens—a large cascading fountain graces Olympic Square, one of the park’s main gathering spaces. To soothe Greece’s hot climate, the fountain is built into a hillside to maximize the cooling effects of its mist.

“It’s helpful to contain fountains as much as possible,” says Grove, “because it’s really the moisture, the temperature, and the winds near the ground that are creating that microclimate atmosphere.”

The shady, misty grotto at Ellinikon’s Olympic Square

For younger park-goers, splash pads are a great way to have fun and stay out of the heat. The design team for Sasaki’s renovation of Boston City Hall Plaza made sure that gathering spaces and playgrounds had interactive water features to keep kids cool. Misting stations can provide similar relief for children and people of all ages, especially runners, cyclists, and others exercising outdoors.

Kids play in a water feature representing Boston’s historic “Great Spring” on Boston City Hall Plaza

City Hall Plaza hosts one of Boston’s most popular playgrounds, which draws families throughout the summer thanks to its cooling interactive fountain and splash pad

Beyond using water to cool the environment, cities can help cool down the public realm by making sure their residents and visitors stay hydrated. The Boston Heat Resilience Plan recommends expanding outdoor drinking fountain and water bottle filling networks in parks, at schools, and at community centers.

One of the worst contributors to the urban heat island effect is the hard, heat-absorbing artificial surfaces of cities, whether it’s the pavement of our streets or the masonry of the buildings around us. The darker a surface is, the more heat it absorbs and the longer it stays warm. On the flipside, brighter surfaces reflect hot rays of UV light up onto the skin and into the eyes of people on the street. Achieving comfort is a balancing act.

The Ellinikon Park in Athens, where designers made sure to line paths and roads with tree plantings, a brighter paving material—one with higher “albedo,” or reflectivity—was used to prevent heat absorption. The shade from the trees keeps the reflectivity from overwhelming pedestrians, while the paved surfaces themselves stay relatively cool.

One place where high-albedo surfaces are unequivocally good is roofs. White roofs, also known as cool roofs, are becoming the industry standard on buildings without solar panels, since they absorb much less heat than traditional asphalt. And since there’s usually no one up there, there’s no need to worry about anyone getting burned by the reflectivity, except for the most extreme of sunbathers.

While writing the Boston Heat Resilience Plan, Tamar Warburg noticed something interesting: many people trying to cool down at community centers turned back at the entrance after being asked for identifying information. For those with vulnerable immigration status or without homes, this imposition was an insurmountable barrier. Warburg realized that these people were turning around and heading to the nearest library, where no identification is required for admission to an air conditioned space with free water and things to do.

“That gave birth to this idea of going to some of these libraries and setting up shaded ‘Cool Spots’ with different types of seating, outdoor wi-fi, misters, and an information table outside of the library so people could be outside in the shade, while having access to the library indoors,” says Warburg. And crucially, no one was asking visitors for identification. It was a hit, and no one was turned back.

As in Boston, cities can augment existing indoor public spaces like libraries with cooling features to strengthen heat resilience in the summer months.

As a part of the Boston Heat Resilience Plan, Sasaki and the City of Boston set up Cool Spot pilots at two branches of the Boston Public Library which included free Wi-Fi and misting tents

Trees, water, cool surfaces, and library cool spots are all great tactics for tackling urban heat. But the most important strategic action cities can take to preserve the public realm in an era of climate change is to set up public institutions that can respond to dynamic weather events as they arise, and steward the health and safety of residents for the long haul.

Boston’s heat plan aims to do this by establishing an Extreme Temperatures Task Force to plan for heat waves and respond quickly and smoothly when they arise. A municipal task force can identify ways to marshall existing resources across city departments and help coordinate their distribution. The plan also sets a goal of green workforce development, laying out a vision to tap into existing training programs at schools and community organizations for new roles in energy retrofits, cool roof installations, and tree planting and maintenance. Some cities are even appointing Chief Heat Officers to coordinate these sorts of efforts.

Strong institutions require bold commitments of resolve and resources from all urban stakeholders—city, state, and federal governments, nonprofit community organizations, and the private sector. Cities can thrive only with a healthy public realm, and as climate change transforms urban life, the summer urbanist solutions developed at studios like Sasaki will be critical tools to strengthen our shared streets and spaces.